'International love and honor' bring fallen Dallas airman's

bracelet to brother

10:29 PM CDT on Saturday, September 26, 2009

By MICHAEL E. YOUNG / The Dallas Morning News

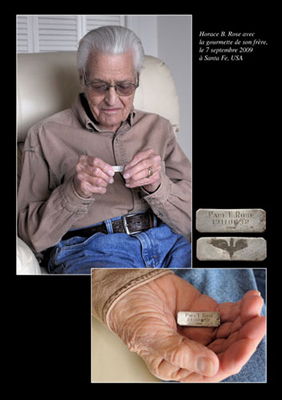

The 50 years it spent in the ground show plainly enough in the scuffs and

scratches on its silver surface.

But for Horace Bryce Rose, few things could be more precious than this old

ID bracelet. It bears the name and service number of his older brother,

Paul E. Rose, who left Dallas to join the Army Air Forces and wore the

bracelet on his final mission on Oct. 8, 1944.

"It's kind of hard to express what I felt when I held this," Horace Rose

said after receiving the bracelet recently. "It was almost as if my

brother was reaching out to me."

Bringing the bracelet back from France took roughly 16 years. But when The

Dallas Morning News wrote about the search for Sgt. Rose's family in July,

readers used genealogical Web sites and property records to find Horace

Rose in a matter of hours.

But in the beginning, there was very little to go on.

Sgt. Paul E. Rose was one of 12 airmen killed when two American B-26

bombers collided as they prepared to land on a captured air strip in the

French countryside.

"They found his pipe, his smoking pipe, in the wreckage," said Horace

Rose, 85 this month and living with a son, "and we got the flag, too, that

covered his casket when he was buried."

But for five decades, this piece of his ID bracelet lay in the earth until

a French farmer found it in his fields.

When Andre Noury realized what it was, his first thought was returning it

to Sgt. Rose's next of kin. And then he considered the almost impossible

challenge of finding the family of a man who died 50 years before.

So he tucked the bracelet away, for more than 15 years. Then, earlier this

year, he learned that people in the nearby village Saint-Peravy la Colombe

were dedicating a memorial to the crew of another B-26 bomber shot down a

week after D-Day.

There, Noury met Christian Dieppedalle, a local history buff, and showed

him what he had found.

Dieppedalle immediately set to work. He found a mention of the midair

crash in a book about the operations of the 394th Bomber Group of the U.S.

9th Air Force, which used the airfield in 1944. The names of both crews

were listed, including Sgt. Paul E. Rose.

Using the Internet and military records, he found Sgt. Rose's sketchy

biographical information. He had been born somewhere in Ohio in 1922,

listed Dallas as his hometown and joined the Army Air Forces in Tucson,

Ariz., in December 1942.

He was 22 when he died.

Then Dieppedalle turned to a Web site dedicated to the crews that

maintained and flew the Martin B-26 Marauder, b26.com. He asked for help,

and got plenty.

Don Enlow of Jena, La., was one of the first to respond. His father had

flown with the 394th, so Enlow offered to do what he could on this side of

the Atlantic. Others quickly joined, too.

"You have Christian, this guy who has been involved with other memorials

to U.S. airmen in France, and this farmer, who walks up to him and says,

'Hey, I found a bracelet and I'm willing to return it to the family if

they can be found,' " Enlow said. "Then a group of people who met on a

privately run social network, an online memorial to Marauder Men, help

find the family in two months."

The final push came when Enlow called The Dallas Morning News, which ran a

story about the mysterious bracelet and its owner's link to the city. In

less than a day, readers found Horace Rose in Santa Fe, living with his

son, his brother's namesake, Paul Rose.

"We got a call from Don Enlow, who called us up and explained the

situation as briefly as he could," Paul Rose said. "We were amazed. We

swapped e-mail addresses and he sent my contact information to Christian

in France and we've become good buddies.

"And we understood how concerned Andre Noury was that we get this

package."

It arrived in Santa Fe earlier this month, Paul Rose said, and when his

dad was feeling well enough, he gave him the package.

"He was deeply moved by it – he and his brother were very close," Paul

Rose said, "but he was good with it. I don't think he let it out of his

hand."

In some ways, having the bracelet brought Horace Rose close to his big

brother again.

"If you didn't know my brother, you wouldn't have any idea how special he

was," he said. "He had an intellect that was in the Mensa class, and he

was a good guy."

After Paul E. Rose went to Europe, Horace Rose joined the Army, too, and

was sent to the South Pacific with the Quartermaster Corps.

And when he learned of his brother's death, he suffered the loss as only a

surviving sibling can, deeply and profoundly, even now.

But at the same time, he's touched that so many people who had never heard

of Sgt. Paul Rose did all they could to bring this small piece of his

brother back home.

"It was fantastic, really," Horace Rose said. "It's an example of real

love, international love and honor. It's amazing." |